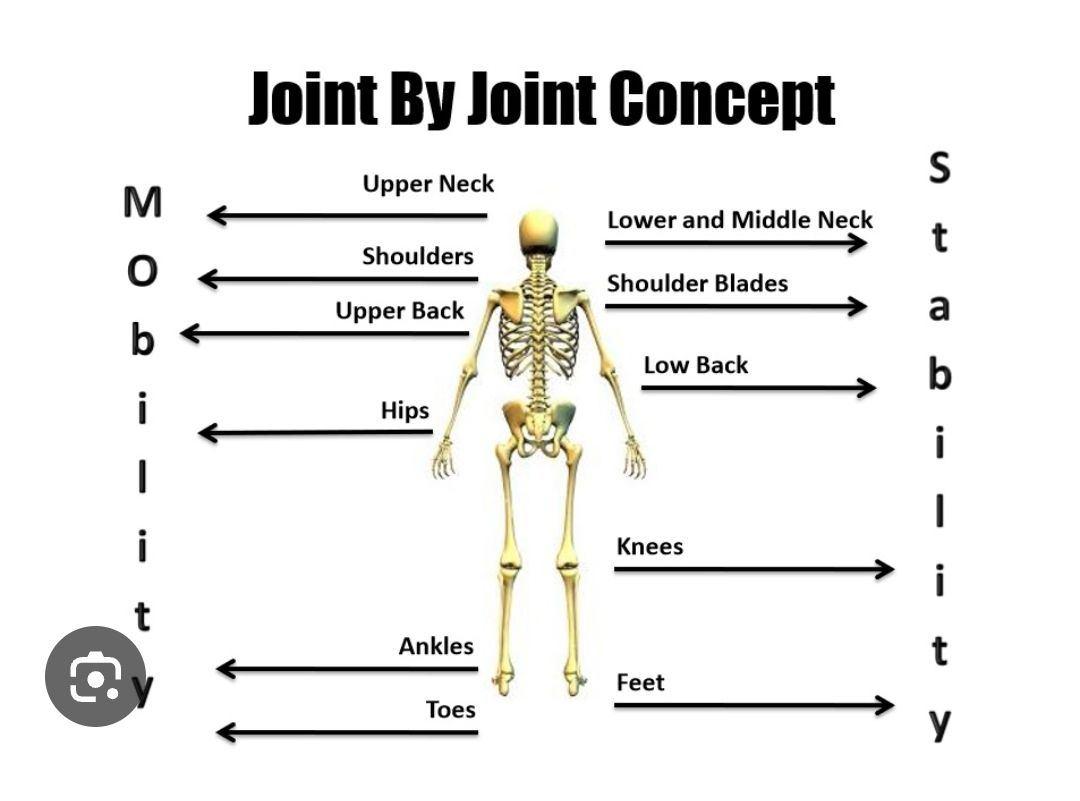

In the early 2000s, two pillars of the strength and conditioning world, Mike Boyle and Gray Cook, met at a seminar to discuss how they each train their members and common issues they encounter regarding individuals’ poor movement quality. A light bulb went off, and they coined the “Joint by Joint approach” to training movement patterns over muscle groups. The rest is history as they say. Today I’d like to share with you the article Mike Boyle wrote about this specific topic and why it is such an important piece of how we write our programs here at On Point Fitness Club.

Over the past 20 years, we have progressed from the approach of training by body part to a more intelligent approach of training by movement pattern. In fact, the phrase movements, not muscles has almost become an overused one, and frankly, that’s progress. Most good coaches and trainers have given up on the old chest-shoulder-triceps method and moved to push-pull, hip-extend, knee-extend programs.

Still, the movement-not-muscles philosophy probably should have gone a step further. Injuries relate closely to proper joint function, or more appropriately, to joint dysfunction. Problems at one joint usually show up as pain in the joint above or below.

The primary illustration is in the lower back. It’s clear we need core stability, and it’s also obvious many people suffer from back pain. The intriguing part lies in the theory behind low back pain–the new theory of the cause: loss of hip mobility.

Loss of function in the joint below–in the case of the lumbar spine, it’s the hips–seems to affect the joint or joints above. In other words, if the hips can’t move, the lumbar spine will. The problem is the hips are designed for mobility, and the lumbar spine for stability. When the intended mobile joint becomes immobile, the stable joint is forced to move as compensation, becoming less stable and subsequently painful.

The Process is Simple

Lose ankle mobility, get knee pain

Lose hip mobility, get low back pain

Lose thoracic mobility, get neck and shoulder pain, or low back pain

Looking at the body on a joint-by-joint basis beginning with the ankle, this makes sense.

The ankle is a joint that should be mobile and when it becomes immobile, the knee, a joint that should be stable, becomes unstable; the hip is a joint that should be mobile and it becomes immobile, and this works its way up the body. The lumbar spine should be stable; it becomes mobile, and so on, right on up through the chain.

Now take this idea a step further. What’s the primary loss with an injury or with lack of use? Ankles lose mobility; knees lose stability; hips lose mobility. You have to teach your clients and patients these joints have a specific mobility or stability need, and when they’re not using them much or are using them improperly, that immobility is more than likely going to cause a problem elsewhere in the body.

If somebody comes to you with a hip mobility issue–if he or she has lost hip mobility–the complaint will generally be one of low back pain. The person won’t come to you complaining of a hip problem. This is why we suggest looking at the joints above and looking at the joints below, and the fix is usually increasing the mobility of the nearby joint.

These are the results of joint dysfunction: Poor ankle mobility equals knee pain; poor hip mobility equals low back pain; poor T-spine mobility, cervical pain.

An immobile ankle causes the stress of landing to be transferred to the joint above the knee. In fact, there is a direct connection between the stiffness of the basketball shoe and the amount of taping and bracing that correlates with the high incidence of patella-femoral syndrome in basketball players. Our desire to protect the unstable ankle came with a high cost. We have found many of our athletes with knee pain have corresponding ankle mobility issues. Many times this follows an ankle sprain and subsequent bracing and taping.

The exception to the rule seems to be at the hip. The hip can be both immobile and unstable, resulting in knee pain from the instability–a weak hip will allow internal rotation and adduction of the femur–or back pain from the immobility.

How a joint can be both immobile and unstable is an interesting question.

Weakness of the hip in either flexion or extension causes compensatory action at the lumbar spine, while weakness in abduction, or, more accurately, prevention of adduction, causes stress at the knee.

Poor psoas and iliacus strength or activation will cause patterns of lumbar flexion as a substitute for hip flexion. Poor strength or low activation of the glutes will cause a compensatory extension pattern of the lumbar spine to replace the motion of hip extension.

This fuels a vicious cycle. As the spine moves to compensate for the lack of strength and mobility of the hip, the hip loses more mobility. Lack of strength at the hip leads to immobility, and immobility in turn leads to compensatory motion at the spine. The end result is a kind of conundrum, a joint that needs both strength and mobility in multiple planes.

Your athletes, clients and patients must learn to move from the hips, not from the lumbar spine. Most people with lower back pain or hamstring strains have poor hip or lumbo-pelvic mechanics and as a result must extend or flex the lumbar spine to make up for movement unavailable through the hip.

In the book Ultra-Prevention, a nutrition book, authors Mark Hyman and Mark Liponis describe our current method of reaction to injury perfectly. Their analogy is simple: Our response to injury is like hearing the smoke detector go off and running to pull out the battery. The pain, like the sound, is a warning of some other problem. Icing a sore knee without examining the ankle or hip is like pulling the battery out of the smoke detector. The relief is short-lived.